Consistency: ACID and CAP

Introduction to consistency problems in distributed systems

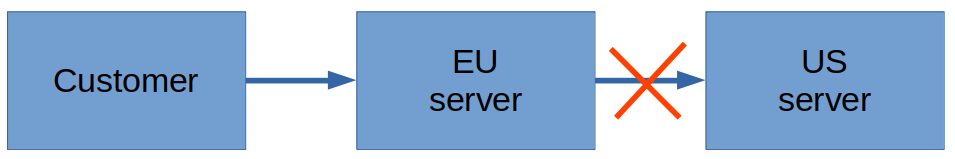

Example problem

A hotel reservation system consists in a server in EU and another in US. A customer connects to the EU server and wants to make a hotel reservation. In particular it wants to enquire if rooms are free and make a booking for a US hotel. The EU server cannot contact the US server for up to date data. What to do?

Knowing the CAP theorem would help give an answer. What’s the CAP theorem and how did we get there?

ACID

This is an acronym standing for “Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation and Durability”. It was developed in the heyday of SQL databases and captured in an ANSI/ISO standard.

The golden example was that of a bank transfer. Say you write code (SQL statements) to transfer an amount from an account to another.

For this transaction:

- Atomicity means that the amount is subtracted from the source account and added to the destination account (or the transaction is entirely aborted). It would be incorrect to only do one of the operations, they must be performed together in an indivisible/atomic fashion.

- Consistency means constraints such as “an account cannot have a negative balance” are respected.

- Isolation means that as multiple requests are executed in parallel, the behaviour is as if they would have been done sequentially.

- Durability means that once a transaction is performed, it will survive system crashes. Usually that means that the results are persisted in a log on the disk and in the case of a system crash, the log can be replayed to recreate the transaction.

To improve performance one could relax isolation requirements, giving way to problems such as dirty reads, non-repeatable reads and phantom reads, or alternatively strengthen the isolation requirement to serializable, where none of these problem occur.

To handle these issues, in practice one had to have an understanding of the lock mechanisms used by the particular database engine used by an application.

The issues with ACID

The certainties provided by the ACID approach come with costs.

One common problem even at relatively small scale is the problem of bulk

updates: data that needs to be updated in bulk. Even a simple statement like

DELETE FROM table WHERE condtion starts to fail at some point because to

maintain ACID criteria, the data to be deleted is first persisted in the log,

just in case the operation fails and has to be rolled back. Eventually that

takes so long that operation times out and fails and is rolled back. Options

exist for this particular case such as deleting only N entries and then

repeat until complete.

Ironically bank transactions, the golden case for the ACID theory, do not follow it. When withdrawing money at an ATM, the bank will happily let the account holder reach a negative balance and charge them penalty fees.

Importantly, Internet scale companies, such as Amazon, followed with the same relaxed approach to consistency for transactions. When you purchase a book, the order will be accepted even in cases where the book is no longer in stock (which does not meet a strict view of consistency of only accepting orders for products you have). When that is the case, instead of straight forward rejecting the order, the seller will first try to source the book (the publisher might have additional stock or the book might be printed on demand). For the rare cases when that fails, you’ll receive an apologetic email. This workflow is justified because there are financial gains from capturing and fulfilling additional orders (as long as the ratio of failures is small).

CAP

CAP as in “the CAP theorem” is an acronym that stands for “Consistency, Availability and Partition Tolerance”. It relates to a conjecture by Eric Brewer in 1998 that a distributed system will not be able to provide all three at the same time. The conjecture has a “proof” by Seth Gilbert and Nancy Lynch of MIT in 2002, hence the “theorem”.

It roughly states that in a distributed system, in the face of partitions (network errors that split the system into parts that are unable to communicate with other parts), it is not possible to maintain both consistency and availability.

Sometimes it’s simplified to state that one can only get two of three, but that’s incorrect, in realistic systems one can get degrees of consistency and availability. Also the “proof” is not convincing, it chooses very specific definitions of the terms involved.

But the importance of the idea is that in distributed systems network errors will occur, and systems overly focused to provide consistency, like the SQL databases, will fail to provide availability, which has business value, as we’ve seen from the ATM case or the book ordering case for Amazon.

Ambiguous terms

The issue with the “proof” comes from the ambiguity of terms.

In everyday life consistency means “to act in the same way over time”.

In logic/mathematics roughly consistency means “free of contradictions”.

For example a formal system is consistent if it cannot be used to derive both a

statement S and its negation not S. But that’s the syntactic definition.

It turns out that there are many variations for the definition of the term,

such as ‘there is an interpretation under which all its theorems are true’

(which is the semantic definition).

In the ACID case, we’ve seen that there was an arbitrary choice between the invariant that “the sum of account balances is not changed by a transfer” (which was put into the Atomicity category) and “an account balance should not become negative” (which was put into the Consistency pot).

Also consistency in CAP has a different meaning from consistency in ACID. The CAP one is focused on reads and writes, rather than invariants.

In the CAP theorem availability can be taken to mean getting a response without the guarantee that it’s the last write, but in practice the content of the response matters and it also has a time dimension: how long does it take to get the response.

The hotel reservation sample

The good news is that practical examples can be worked out.

In our initial example if the EU server can contact the US server (no partition) then all is good, we can check if rooms are free and record the booking. This gives both consistency (correct data) and availability (customer can perform the booking) when there are no partitions.

However if the EU server could not contact the US server due to network errors, then we cannot have both consistency and availability.

One approach is to propagate the error to the client: “Sorry, unable to make enquiries for this hotel at the moment”. This would choose consistency instead of availability. The issue with that is that it leads to lost business. Customer might have lost interest/checked a competitor by the time the network connectivity is restored.

Another approach is to pretend rooms are available and accept the bookings anyway. This would choose availability instead of consistency. The issue with that it that we can end up with rooms over-booked.

A third approach is to know that often hotels are not 100% booked. So we can accept some reservations, based on previous data such as recently synced room status or known seasonal trends, providing availability for a while in the hope that the network connectivity can be restored. This is an example of a trade-off of consistency and availability in face of partitions.

Generalization

Similar ideas apply to other distributed systems, not just to databases, e.g. in a multithreaded environment there are choices for the delay at which the system becomes consistent: to propagate a “cancel work” boolean flag do you wait for the other thread to acknowledge it? If yes then you’ll do waiting reducing availability, if no then you’ll have to handle the case of work completing after you initiated the cancellation.

References

- Eric Brewer: CAP Twelve Years Later: How the “Rules” Have Changed, 30 May 2012