Controlling the controller

Demonstration of the software stack I’m using for a project to manage a micro-controller using a web browser user interface.

What it is

This is a demo for a prototype application that I’ve put together in my spare time for a friend. It allows a user to change settings for a micro-controller through a web browser interface.

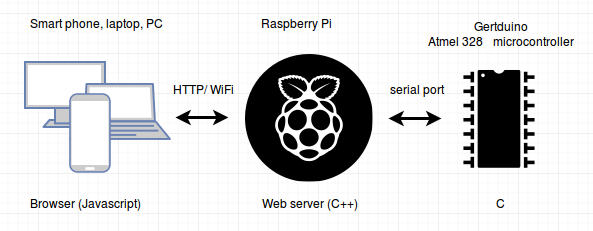

This image shows the high level architecture. It involves three devices:

- a laptop or PC or smartphone etc.

- a micro-controller (an Atmel Atmega-328, on a Gertduino board)

- and a Raspberry Pi in the middle.

The user uses a browser on a laptop, PC, smartphone etc. The browser displays two sliders that the user can drag. The Gertduino board has a number of leds. The sliders control the settings for which led to blink, and for the blinking speed.

Raspberry Pi acts in the middle as web server for the browser on one side and communicates with the micro-controller through the serial port on the other side.

How it works

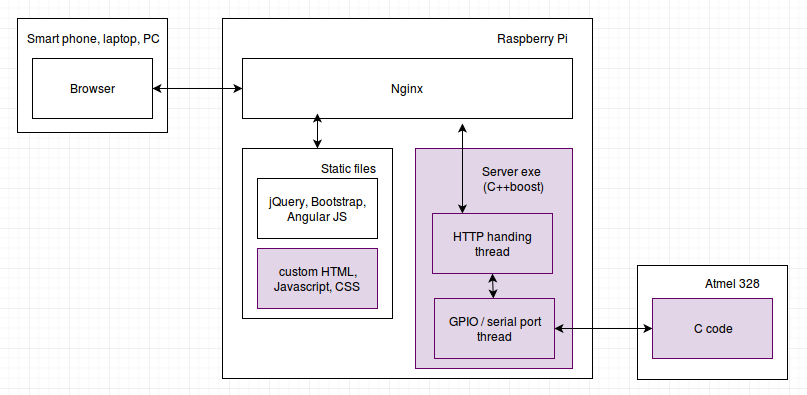

This image shows in more details the software stack involved. The boxes with a grey background show the components I wrote for the prototype (and the languages used).

The user points a browser on his device to the Raspberry Pi.

On the Raspberry Pi, Nginx is running as a web server on port 80. Depending on the request path, Ngnix will either deliver files or route the request to a separate server process.

To start with, it will deliver static files (from the server point of view): HTML, CSS and JavaScript files which are the web application that the browser runs. The web application uses Bootstrap as a framework for look and feel, and Angular JS as a framework for the dynamic behaviour (from the browser point of view). Using these frameworks, little custom code is required to displays the two sliders and make Ajax requests back to the web server to get and set the values of the sliders.

Nginx routes these two requests to a separate server process. This process is written in C++, using boost, and has two threads. One thread asynchronously handles HTTP requests, using boost asio. The other thread deals with controlling the Gertduino board. It accesses the GPIO to ensure the reset flag is off, and the serial port to update the micro-controller with the values of the sliders.

The micro-controller runs code written in C, that uses interrupts to handle communication over the serial port and flashes the leds based on the received values.

Why this way

The user devices market is very fragmented. We have Windows PCs, Macs, iPhones, Android phones, tablets etc. To write and test native applications across many platforms would require significant effort. Hence the browser application choice.

Bootstrap, Angular JS handle most of the browser/screen resolution variability.

At the other end, micro-controllers are cheap and handle the real-time constraints of the application, but are not powerful enough to handle HTTP well. Hence the Raspberry Pi board.

The web server could have been cloud hosted, but for this application, based on the anticipated usage scenarios we decided to host the web server on the Raspberry Pi.

Nginx as a reverse proxy is a no-brainer. It routes the requests and serves the static files. It also means that the server process only needs to implement HTTP 1.0.

The server process is written in C++. It could have been written in Python as well. It’s a matter of control/precision/quality vs. speed of development. Usage of boost asio in particular made it possible for a single thread to concurrently handle multiple HTTP requests in parallel.

The separate control thread ensures that we can have long control operations while the HTTP thread continues to be responsive. It also allows us to change to a cloud hosted scenario in the future (the HTTP server thread would then become a HTTP client thread connecting to the cloud hosted server).