CPU memory model

Modeling CPU concurrency

Sample

Let’s say that on an x86 processor, starting with two memory locations x and

y set initially to 0, we run two threads (or processes).

The first one executes:

1

2

mov [x],1 ; store 1 at the location x in memory

mov eax,[y] ; load value from location y in memory to register eax

while the second one executes:

1

2

mov [y],1 ; store 1 at the location y in memory

mov ebx,[x] ; load value from location x in memory to register ebx

The question is: what are the possible states for the eax register of the first

thread and for the ebx register of the second thread?

At a first look it seems that, since each writes first 1 to a location before

reading the other location, it should be that at least one register is set to

1 if not both. This would certainly be true if the processor would be

sequentially consistent, i.e. the instructions of the two threads could be

interleaved, but the relative order is maintained.

But it turns out that it’s also possible that both eax and ebx end up 0.

Speculative execution

Many modern processors do speculative execution. In one type of speculative execution the processor might estimate what are the chances that a conditional branch will be taken and execute the instructions following it. If the guess was correct, the processor is well ahead compared to just waiting. If the guess was wrong, the processor tries to revert the effects of the instructions that it executed speculatively.

The paradox in the example above is not due to speculative execution. It happens even within the official, proper behaviour of the processor, described in terms of an abstract machine.

As a side note, Meltdown and Spectre are examples of security vulnerabilities that result from cases where there are observable effects for the instructions executed speculatively. An attacker obtains information based on side effects (side-channel) outside the abstract machine description. E.g. speculative execution impacts caches, and an attacker can check if a memory location is cached (based on the speed of access) to infer the results of a speculative execution of reads from memory it should not have access to.

Data dependency ordering

Data dependency from the CPUs point of view are cases where it’s clear that two instructions depend on each other. E.g. when reading a location from memory to later use that value as a pointer to access another location, the CPU can infer that the two operations are related and should not be reordered. Most of the processors respect data dependencies ordering. This is the case for x86 processors. One exception is the DEC Alpha processor that is in a league of its own.

In the example above each thread executes instructions that relate to different memory locations, so the data dependency ordering by the x86 processor does not stop out of order execution.

Weak and strong memory models

When instructions refer to different memory locations, with regards to loads/reads from memory and stores/writes to memory there are 4 possible issues:

- writes can be reordered ahead of other reads

- writes can be reordered ahead of other writes

- reads can be reordered ahead of other reads

- reads can be reordered ahead of other writes

x86 processors only have the last issue. In the example above the read

instructions follow write instructions to another memory location. The

processor appears to perform the read ahead of the write, leading to the

outcome where both reads end up with the initial value, 0.

But other than this particular case, x86 processors do not have the other 3 issues. These kind of processors are said to have strong memory models.

Other processors, like ARM, PowerPC can exhibit any of the 4 possible issues. These kind of processors are said to have weak memory models.

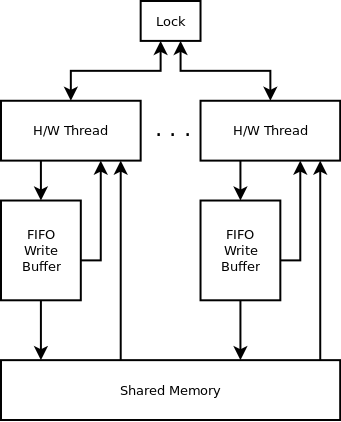

TSO model for x86

Another way to be able to predict the x86 processor behaviour is to have a model where each hardware thread has a FIFO buffer for writes, while reads are not immediate, not buffered. When reading a memory location, it is first looked up in the FIFO buffer for writes. This is known as the total store ordering model.

Using this model, even if the hardware thread executes the instructions in order, in our example the writes might still be in the FIFO buffer for writes, and the reads happen directly from the memory before the content of the buffer is written to the memory.

A global lock is sometimes used to ensure exclusive memory access e.g. to flush the FIFO write buffer for some instructions. I would not be surprised if this behaviour allows a thread to influence other threads Meltdown/Spectre style.

Memory fences

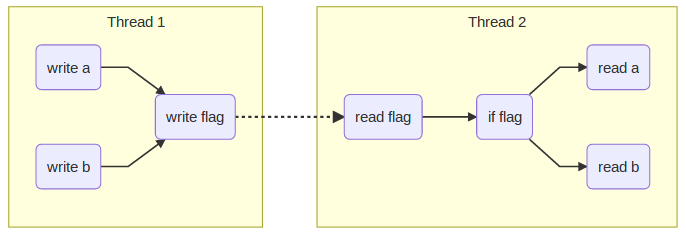

One common scenario of communicating between two threads involves the following scenario:

- One thread, the producer thread, writes several pieces of data, say

aandb, then it sets aflag. - Another thread, the consumer thread, checks the

flagand when set, it then readsaandb.

From the point of view of the programmer there is an implied dependency as

shown in the following graph using solid lines. For example in this case it

does not matter in which order a and b are written, but it does matter that

both a and b are written before the flag is written: we don’t want the

producer to read the flag and infer that it can then read a or b before

they were set to the intended values.

These dependencies are the intention of the programmer, but the CPU cannot

identify them when a, b and flag are at different memory locations.

The academic approach is to refer to memory barriers. For example (not a formal definition):

- write-release: e.g. ensure that all writes are performed BEFORE

the write to the

flag. - read-acquire: e.g. ensure that all reads are performed AFTER

the read of the

flag.

Sometimes an explicit CPU instruction is required to achieve the desired behaviour. Other times the barrier can be achieved with no additional CPU instruction, implicitly, based on the strong memory model provided by the processor.

As a side note, sometimes there are special situations where the amount of data is small, involves a single memory location and there might be atomic instructions that allow to achieve the intended behaviour with less overhead.

Conclusion

We’ve seen that memory models describe the possible reordering of memory accesses by a processor

This creates a classification of CPUs into:

- very strong, sequentially consistent e.g. single threaded, unoptimised CPUs

- strong memory model: e.g. x86

- weak memory model: ARM, PowerPC

- very weak memory model: DEC Alpha

This classification is just a starting point, details matter, and processor documentation does not always provide all the required information.

References

- Peter Sewell, Susmit Sarkar, Scott Owens, Francesco Zappa Nardelli, Magnus O. Myreen: x86-TSO: A Rigorous and Usable Programmer’s Model forx86 Multiprocessors, 17 May 2010

- Jeff Preshing: Weak vs. Strong Memory Models, 30 Sep 2012

- Bill Pugh: Reordering on an Alpha processor

- Lockless Programming Considerations for Xbox 360 and Microsoft Windows