Threading before C++11

Threading was possible before C++11. How did it work?

Simple example

The C++ standard only referred to single threaded programs before C++11. And yet all major operating systems and compilers supported multi-threading programs well before C++11.

On Windows a program can create threads with CreateThread and then a mutex

can be used to allow exclusive access to a resource. A mutex is created with

CreateMutex which returns a HANDLE. To get exclusive access a thread will

wait for the mutex HANDLE. WaitForsingleobject is one of the many

functions that can wait for Windows HANDLEs. To end the exclusive access the

thread calls ReleaseMutex.

Below is an example that tries to show how compilers handled multi-threading before C++11, but it’s pointless outside this purpose (it’s also a bad example of error handling and resource management).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

#include <Windows.h>

#include <iostream>

int fib(int x)

{

if (x < 2) return 1;

return fib(x - 1) + fib(x - 2);

}

DWORD WINAPI ThreadFn(LPVOID)

{

return 0;

}

int main()

{

int result = fib(39);

auto m = ::CreateMutexW(NULL,NULL,NULL);

result = fib(40);

auto h = ::CreateThread(NULL, 0, ThreadFn, &result, 0, NULL);

result = fib(41);

::WaitForSingleObject(m, INFINITE);

result = fib(42);

::ReleaseMutex(m);

::WaitForSingleObject(h, INFINITE);

std::cout << result << '\n';

return 0;

}

Discussion

From the point of view of the compiler, all the Windows functions we use in the

example (CreateMutex, CreateThread, WaitForSingleObject, ReleaseMutex)

are implemented in external DLLs, the compiler has no visibility into their

implementation, they could have side effects. I’ll call them external

functions.

To start with, the relative order of external functions is preserved.

Also typically when threads access a common piece of data they need to know the

address of that data, for example pass it somehow. The example above simulates

that by passing the address of the result variable from the main thread to

the CreateThread function. This being a dummy example it does not really use

it from the created thread, but it’s enough to show the compiler behaviour.

From the point of view of the compiler, once the address of a variable is passed to a external function, it has to treat access to that variable more carefully, because it needs to assume that the external functions can hold that address and access it. That variable has to have an actual address in memory, can’t be manipulated solely in CPU registers, and the compiler cannot rely on the value from a register across a call to an external function. Instead values have to be read from memory after an external function call, and written to memory before an external function call.

For example the result variable has to have a memory location to which a

mov assembly instruction to that memory location has to be generated before

any call assembly instruction into an external function.

This does not extend to code that the compiler has solely visibility of, such

as the calculation performed by the fib function. The compiler can re-order

that, as long as it’s done before the assignment to result.

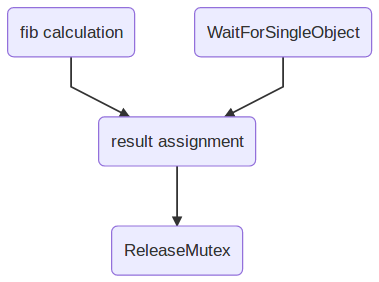

For example the dependency graph that the compiler uses for the

WaitForSingleObject to ReleaseMutex section looks like below. The fib

calculation can be reordered before WaitForSingleObject, but the assignment

to result is sandwiched between WaitForSingleObject and ReleaseMutex.

The compiler also has to identify more indirect cases, to start with the

result could have been member of a struct and the address of the struct

instance passed across. Or it could have been a global variable.

The compiler’s job is limited. It is the job of the external functions to

generate the appropriate memory fences (either explicitly or implicitly). E.g.

WriteForSingleObject for a mutex should at least generate a read-acquire

fence and ReleaseMutex should at least generate a write-release fence.

As a side note: the Windows mutex is a relatively heavy approach which has the

advantage that it can be used across processes. For a lightweight approach

inside the same process there are Windows critical sections or std::mutex

from C++11.

The problem before C++11 is that if developers tried to provide themselves multi-threading primitives there was little formal guarantees from the compiler, operating system and processor specifications. With regards to multi-threading in particular just because the code seems to work is not guarantee that it always really works.

Conclusion

Before C++11, the C++ standard only referred to single threaded applications. While in practice multi-threaded applications were written, and compilers restricted optimisations around external functions, someone had to implement those functions. Threading cannot be implemented as a library without compiler support. Without clear specifications even experts struggled, examples were Linux kernel locks, Java VM garbage collectors etc.

Appendix: generated code

For reference, here is an example of the generated assembly code for the example above:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

17: int result = fib(39);

mov ecx,26h

call fib (0F01000h)

mov ecx,25h

mov esi,eax

call fib (0F01000h)

18: auto m = ::CreateMutexW(NULL, NULL, NULL);

push 0

push 0

17: int result = fib(39);

add eax,esi

18: auto m = ::CreateMutexW(NULL, NULL, NULL);

push 0

mov dword ptr [result],eax

call dword ptr [__imp__CreateMutexW@12 (0F03000h)]

19: result = fib(40);

mov ecx,27h

18: auto m = ::CreateMutexW(NULL, NULL, NULL);

mov dword ptr [ebp-0Ch],eax

19: result = fib(40);

call fib (0F01000h)

20: auto h = ::CreateThread(NULL, 0, ThreadFn, &result, 0, NULL);

push 0

push 0

19: result = fib(40);

mov edi,eax

20: auto h = ::CreateThread(NULL, 0, ThreadFn, &result, 0, NULL);

lea eax,[result]

push eax

push offset ThreadFn (0F01030h)

push 0

19: result = fib(40);

lea ecx,[edi+esi]

20: auto h = ::CreateThread(NULL, 0, ThreadFn, &result, 0, NULL);

push 0

mov dword ptr [result],ecx

call dword ptr [__imp__CreateThread@24 (0F0300Ch)]

21: result = fib(41);

mov ecx,28h

20: auto h = ::CreateThread(NULL, 0, ThreadFn, &result, 0, NULL);

mov ebx,eax

21: result = fib(41);

call fib (0F01000h)

mov esi,eax

22: ::WaitForSingleObject(m, INFINITE);

push 0FFFFFFFFh

push dword ptr [m]

21: result = fib(41);

lea ecx,[esi+edi]

22: ::WaitForSingleObject(m, INFINITE);

mov edi,dword ptr [__imp__WaitForSingleObject@8 (0F03004h)]

mov dword ptr [result],ecx

call edi

23: result = fib(42);

mov ecx,29h

call fib (0F01000h)

24: ::ReleaseMutex(m);

push dword ptr [m]

23: result = fib(42);

add eax,esi

mov dword ptr [result],eax

24: ::ReleaseMutex(m);

call dword ptr [__imp__ReleaseMutex@4 (0F03008h)]

25: ::WaitForSingleObject(h, INFINITE);

push 0FFFFFFFFh

push ebx

call edi

26: std::cout << result << '\n';

push dword ptr [result]

mov ecx,dword ptr [_imp_?cout@std@@3V?$basic_ostream@DU?$char_traits@D@std@@@1@A (0F03058h)]

call dword ptr [__imp_std::basic_ostream<char,std::char_traits<char> >::operator<< (0F03044h)]

mov ecx,eax

call std::operator<<<std::char_traits<char> > (0F011D0h)

References

- Hans-J. Boehm: Threads Cannot be Implemented as a Library, 12 Nov 2004