How vector works - push_back

A close examination of the push_back operation for vector.

Introduction

push_back adds a value to the end of the array managed by the vector.

std::vector does not provide a push_front operation. The convention for the

STL containers is to provide such operations only if they are more efficient

than a plain insert. For std::vector, that’s the case for push_back, but

not for a potential push_front.

Amortised constant time

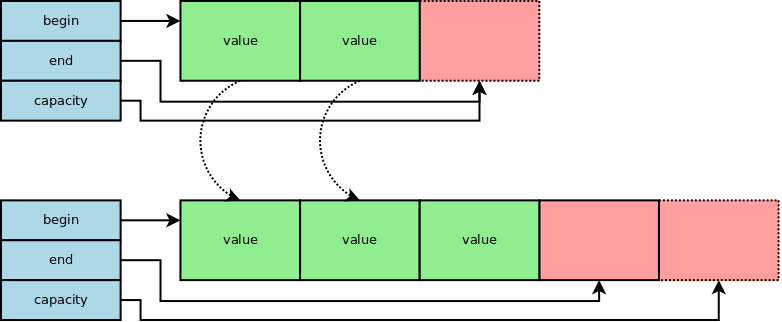

The implementation for the std::vector::push_back first checks if there is

space by comparing the end pointer with the capacity pointer. Different

values indicates there is space.

If there is space the value can be copied/moved, and the end pointer

incremented. This case has obvious O(1) time complexity.

If there is no space in the existing array:

- a larger array needs to be allocated

- the new value is constructed at the correct position in the larger array (this is done at this point in case it references existing values)

- the existing values copied/moved across

- the old values are destroyed

- the previous smaller array is deleted

- the

begin,endandcapacitypointers adjusted accordingly.

So when the capacity has to be increased, this incurs O(N) operations

(copying across the N existing values).

However push_back is quite efficient, having an amortized constant time

complexity. This is despite the worst case of O(N). Amortized means that

not each operation is constant time, but overall, if the operation is performed

repeatedly (i.e. if you keep on adding values with push_back), then cost is

still a fixed number of operations per push_back.

The way it achieves that is by resizing when growing not with a fixed increment, but with a proportional one. Typically vectors grow 1.5x (e.g. Microsoft) or 2x (e.g. g++) of their current size.

Vector vs. list

What container type should you choose for the code below?

1

2

3

for (size_t i = 0; i < N; ++i) {

container.push_back(value);

}

Specifically should you use a vector or a list, which one is more efficient?

If you choose a list the cost per push_back is:

- A allocation of a list node

- A copy/move of the value into the node

- Some pointers/size adjustments (about 5 values)

For the vector choice let’s look at the operations costs for a vector growth

strategy of 2x, for the worst case, when the vector just had to be resized to

insert the Nth element:

- We just copied/moved

N-1elements. We did the same previously for half, a quarter etc. The total cost of all these copies is2*N - 3. That’s about 2 copy/moves perpush_back log(N-1) + 1array allocations (and pointer adjustments)- A copy/move of the value into the array

- The end pointer adjustment

So the difference comes mainly to comparing:

- For the list: a allocation for a list node

- For a vector 2 copy/moves

For most value types, especially for commonly used ones like int,

std::string, the vector wins, using a list is an anti-pattern.

Another anti-pattern is to try to manage the resizes manually too aggressively, negating the advantages of the vector growth strategy:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

// inserts at the end anti-pattern

void fn(std::vector<std::string> & c)

{

for(/*some loop here*/)

{

c.resize(c.size() + 1);

c.back() = value;

}

}

An additional reason why the vector is fast comes to the fact that it uses a memory contiguous layout. To start with, this results in an efficient usage of the memory where values are stored one after the other, compared with e.g. the list that requires memory for at least an additional pointer with every value. Also like for arrays, processors notice the access patterns so, e.g. for a linear traversal of the data, the processor will pre-fetch data from memory to the cache, compared with e.g. the list where the processor has to first fetch the next node before it has the address of the following value.

Excess space

The growth strategy comes with the side effect of additional excess space that is unused.

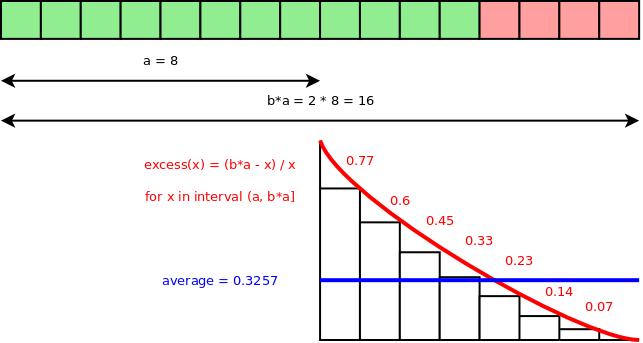

In the diagram above, the array was resized from size a of 8 values, using a

grow factor b of 2, to a new array of a * b of 16 values. After that, more

values were added taking the used size of the vector to x of 12 values. But

the remaining 4 entries are excess unused space size where the excess as a

ratio of the used space can be calculated as (b * a - x) / x of 33%. For a

vector of random size between 9 and 16, the average excess is 32.57%.

The N4055 paper claims that the excess is “an average of 20% for VC’s 1.5x growth, or 33% for 2x growth”. But using the program below the average I got for 2x up to size of 1024 was got: 38%.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

import math

for growth, limit in [(1.5, 1066), (2, 1024)]:

excess = []

capacity = 1

for i in range(1, limit):

if i > capacity:

if capacity == 1:

capacity += 1

else:

capacity = math.floor(capacity * growth)

excess.append(float((capacity - i)/i))

average = math.fsum(excess) / len(excess)

print("For growth", growth, "average excess is", average)

# prints:

# For growth 1.5 average excess is 0.21201090170295975

# For growth 2 average excess is 0.3816378943614083

We can use calculus to at least establish an upper bound in the range a to b * a:

It turns out that the value does not depend on a, therefore it’s an upper

bound for the whole range. So we get upper bounds of 38.6% or 21.6% (for 2x or 1.5x)

respectively.

Therefore different growth strategies are a compromise between resizing less

often, leading to less operations per push_back, and having less

excess/unused space in average.

References

Ville Voutilainen et al. N4055: Ruminations on (node-based) containers and noexcept - 2014-07-02