How vector works - basic

The basics of the std::vector, the default container in C++.

This article describes a simplified mental model on reasoning about a typical

std::vector, without getting into too much details.

A vector is a variable sized array of values.

Layout

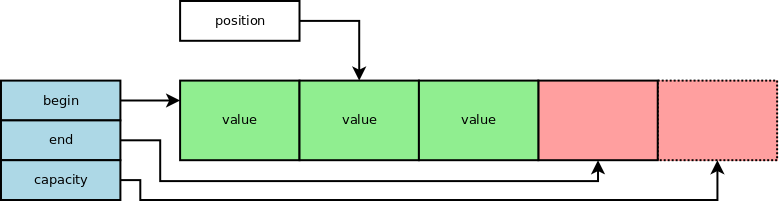

In member variables it holds:

- a pointer to the array:

begin - a pointer one past the last used element in the array:

end - and a pointer one past the last usable element in the array:

capacity

end and capacity could be sizes instead. It all comes to the economy of

calculations. An iterator (position) in the vector uses a pointer as well, it

might be easier to two pointers to check if it reached the end.

The array is usually allocated on the heap.

The memory used by a vector is:

- three pointers

- plus whatever the allocated array is

In the diagram above there is space for 4 values, but only three are used.

The vector is a template class. It takes as template parameters:

- the type of the values in the array

- an allocator (not used often)

The type of the values in the array is exposed back by the vector as

value_type.

Usage

First of all the vector has constructors:

- the default constructor creates an empty vector

- there are constructors to copy data from other ranges

- there is a constructor to build a vector of a certain size

Here is a vector x of 20 ints.

1

std::vector<int> x(20);

This is one of the cases where you usually don’t want to use the braces initializer:

1

2

std::vector<int> x(20); // creates a vector of 20 ints, all have value 0

std::vector<int> y{20}; // creates a vector of 1 int, the value of which is 20

The destructor will destroy the array (and the used elements in the array).

Copy makes a copy of the values from the right side into the array owned by the vector on the left side. It is deep, it does not only copy the pointers.

Move operations transfer the ownership of the array. In a way, it’s the move operation that copies the pointers (and sets)

Then there are methods to access the range of values in the vector:

begin,endandsizerbegin,rendandconstoverloads- index operator, that gives us random access

To enumerate data in a vector:

1

2

3

4

for (auto it = x.begin(); it != x.end(); ++it) {

// where the type of `it` is `std::vector<int>::iterator`

// use data at `*it`

}

or via the syntactic sugar of the range-based for loop:

1

2

3

4

5

for (auto& value : x) {

// use const auto& for read only

// otherwise type of `value` is `int&`

// use data at `value`

}

or by index:

1

2

3

for (size_t i = 0; i < x.size(); ++i) {

// use data at `x[i]`

}

datagives us direct access to the underlying arrayemptytells if the array is empty (it’s an adjective, not a verb), a better name would have beenis_empty.frontandbackgive direct access to the first or last element (assuming the array is not empty)

Resizing

To add values (increasing the size of the vector)

insertto insert at a given positionpush_backto insert at the back

These operations increase the size of the vector. Eventually more space is needed. The vector then allocates a new larger array and moves/copies the values from the old array into the new array, before disposing of the old array.

The insert has a O(N) complexity for random insert positions. But

push_back has amortised constant complexity (amortized O(1)), and I’ll

cover this in details in the next article.

To control resizing one can use:

resizewhich allocates a larger array if needed, but it only adjusts size when shrinkingshrink_to_fitfrees unused memory when shrinkingcapacityreturns the size of the underlying array.

When resizing occurs existing iterators are invalidated, they should not be used because they point to the old deleted array.

1

2

3

4

5

std::vector<int> x(20);

auto front = x.begin();

*front = 42;

x.push_back(43);

// do not use `front` here

Conclusion

std::vector is a relatively thin wrapper around an array. It adds the ability

to resize. It comes with all the risks involved in accessing data without bound

checks, but also with the efficiency of access and compactness of memory.