AWS S3 consistency history

A case study of how the evolution of Amazon S3 consistency is linked to issues postulated by the CAP theorem. An example of eventual consistency.

What it is

Amazon Web Services (AWS) is a subsidiary of Amazon offering pay-by-usage cloud computing services. S3 stands for Simple Storage System, practically it is the first service offered by AWS, since 2006, and it’s a data storage facility.

In practice you can store files (called objects) in folders (called buckets) that you access by file name (called key) via HTTP:

PUTrequests upload the fileGETrequests retrieve the fileDELETErequests delete the file

The consistency model of S3 evolved over time and makes for an interesting case study. It received a major change around January 2021.

Pre 2021 S3 consistency model

Documentation

Before 2021, the documentation for S3 had the following to say about its consistency:

Amazon S3 provides read-after-write consistency for PUTS of new objects in your S3 bucket in all regions with one caveat. The caveat is that if you make a HEAD or GET request to the key name (to find if the object exists) before creating the object, Amazon S3 provides eventual consistency for read-after-write.

Like in the ACID case, where ANSI wording was not enough, one needed to understand the locks employed by a specific SQL engine, statements like this are somewhat cryptic when trying to understand what it means in practice: “read-after-write consistency” sounds academic, but what does “read-after-write consistency with one caveat” is supposed to mean?

System model

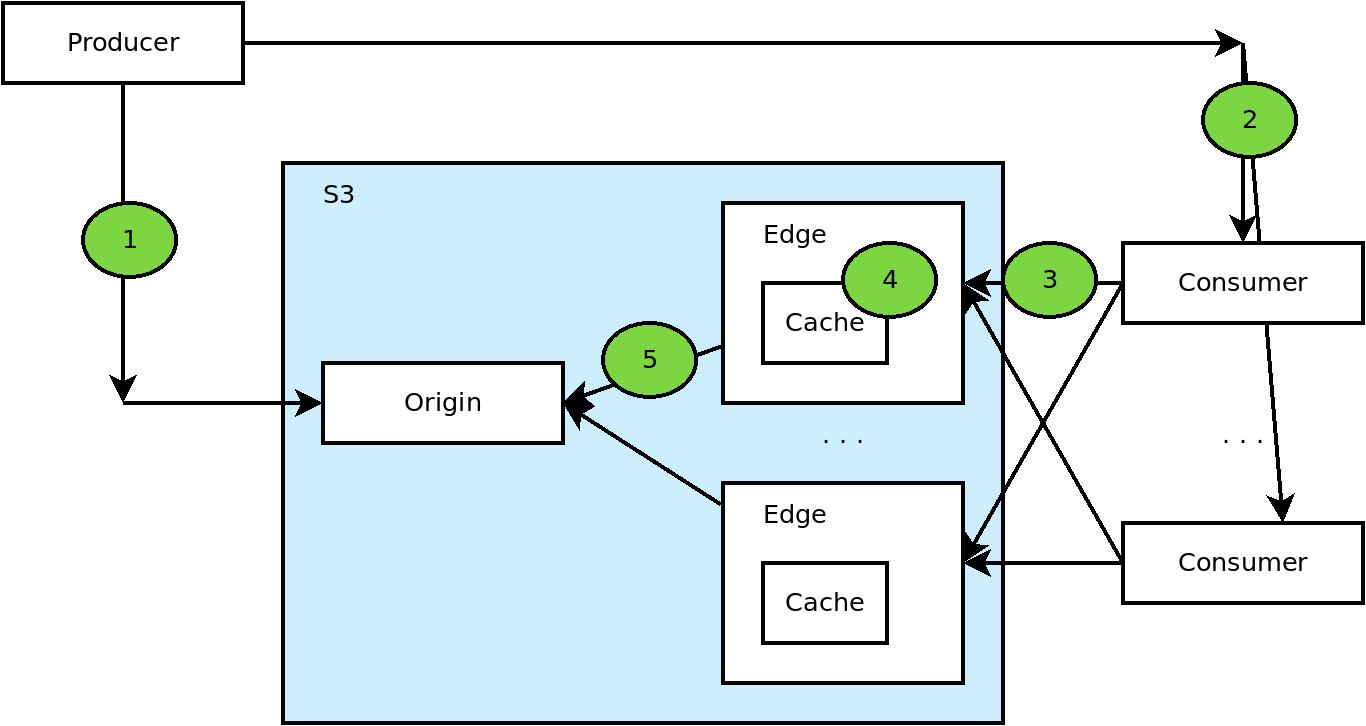

It is easier to understand what it means, if you have a system model. Amazon S3 documentation did not provide such a model unfortunately, but here is one that I produced based on the observable side effects.

It describes a typical scenario where a producer uploads a file and consumers retrieve it, all via S3. The S3 system is split into origin, the absolute source of truth about the contents of a file, and a number of edges that are really reverse proxies with local caches that serve the content. For scalability of distribution there are many edges and the local cache serves as a temporarily store for the file contents so that origin does not have to be checked for every retrieve request.

Happy path

With the bullet numbers corresponding the ones in the diagram above:

- The producer uploads a file using a

PUTrequest - The producer communicates the file name to the consumers (that can be using methods outside S3)

- Consumers make

GETrequests to retrieve the file content. Different requests can reach different edges, even when the requests are made by the same customer. - The edge checks its local cache, the file is not present for the first request, but it will be ready available for subsequent requests until the cache ages

- If the file is not in the local cache of an edge, the file is retrieved from the origin and cached for a while. Consumer gets the file content.

In terms of requests to S3 this means for example:

PUT /bucket/file.png (file content) 200

GET /bucket/file.png 200 (file content)This is described as read-after-write in the documentation meaning that

because the GET request (the read) is made after the PUT request (the read)

it will get the file contents, as opposed to a file not found error.

Stale data for updated content

If the file is updated from version 1 to version 2, then the following sequence is possible:

- The producer uploads version 1 of the file using a

PUTrequest - Consumer retrieves version 1 from an edge, edge A, which caches the content

- The producer updates the file to version 2 using a

PUTrequest - Consumer retrieves version 2 from edge B (edge B did not have the previous version cached, so it reaches the origin and retrieves the latest version)

- Consumer retrieves version 1 from edge A (which continues to deliver version 1 from cache until cache ages and version 1 is purged)

- But eventually version 1 is purged from all caches and consumers will only retrieve version 2

In terms of requests this means for example:

PUT /bucket/file.png (file version 1) 200

GET /bucket/file.png 200 (file version 1)

PUT /bucket/file.png (file version 2) 200

GET /bucket/file.png 200 (file version 2)

GET /bucket/file.png 200 (file version 1)

GET /bucket/file.png 200 (file version 2)This behaviour leads to stale data (older content) when the content of a file is updated. It comes with consequences such as:

- different consumers receive different versions

- the same consumer can alternatively receive old and new content

- if a set of files are delivered, the consumer could fetch an mixture of old and new content

Missing data for re-created content

If the file is deleted and then re-created, then the following sequence is possible:

- The producer deletes an existing file using a

DELETErequest - The client then tries to retrieve the file using a

GETrequest. The edge returns 404 (file missing), and caches the outcome - The producer re-creates the file using a

PUTrequest - The client tries to retrieve the file using a

GETrequest. If it hits the edge that cached the 404, it will get 404 instead of the file content until the edge cache edges.

In terms of requests this means for example:

DELETE /bucket/file.png 200

GET /bucket/file.png 404

PUT /bucket/file.png (file version 2) 200

GET /bucket/file.png 404The behaviour is similar to issue above with many possible outcomes of either getting the file content or getting 404 results intermittently.

Eventual consistency

However in both cases if the producer stops updating the content, eventually the caches will age, the edges will fetch the last version from origin, so eventually the consumers will get the last content. That’s what it is meant by eventual consistency.

In terms of requests this means for example:

PUT /bucket/file.png (file version 2) 200

GET /bucket/file.png unpredictable for a while: version 1 or 2, or even 404

... but eventually all get requests retrieve the content

GET /bucket/file.png 200 (file version 2)Many meanings for “consistency”

We’ve focused here on the consistency of the content of a single file, but there many other aspects. For example when several files are added/deleted from a bucket what is the expected result of listing the contents of the bucket? How about when buckets are deleted/created or their settings are changed? There might be additional application consistency issues as we’ve seen in the hotel reservation example in the previous article.

Post 2021 S3 consistency model

Around January 2021, the S3 consistency model was updated.

Originally S3 was largely used for say images in a web site (or similar scenarios). The image files would be updated from time to time and eventually the browsers will get the last version by refreshing.

But over time more of the use cases involved processing data files. Handling the inconsistencies results in either: wasted repeated processing, or additional complexity to handle the inconsistencies, or usage of libraries on top of S3 to avoid the inconsistencies. Also because the inconsistencies are rare and transient it surprises users/developers leading to additional diagnosing/application development effort.

So the new documentation starts with:

Amazon S3 provides strong read-after-write consistency for PUTs and DELETEs of objects in your Amazon S3 bucket in all AWS Regions.

The clear outcome is that the consistency has been improved compared with the previous model. “strong” is technically redundant, but the intent is to draw the attention that the model changed and it does not have “caveats” as before.

The announcement of the change is a bit more marketing than purely technical. It focuses on example of customers that are happy with a change. And they’re probably right about that, a lot of their customers will be happy with the change. They also insist that they’ve done a lot of testing to ensure consistency is stronger. Well … you have to :)

But [some of the info][s3-desgin-info] is questionable:

we wanted strong consistency with no additional cost, applied to every new and existing object, and with no performance or availability tradeoffs

I mean I do not question that they wanted, but to achieve it they will break the CAP theorem, which probably they did not. So probably what they meant is that given the availability they commit to, having been able to squeeze additional improvements in system availability over time, rather then provide increased availability, they traded it for increased consistency, because that’s what they thought their customers want.

On models

Models come with limitations.

That’s not different from say a model of a solar system. That’s useful to illustrate orbits and explain Earth’s days and seasons, but it might be held by wires and not to scale.

Similarly the TSO model for Intel x86 CPUs does not mean that processors are actually build physically that way.

The model above for the pre 2021 S3 consistency model does not explain how come

the PUT requests are routed to the origin, so it’s not useful for

implementing a S3 system yourself, but it’s useful for reasoning about the S3

behaviour.

It would be useful if Amazon would provide a model for S3, but they don’t.

References

For more info on the new 2021 S3 consistency model see: